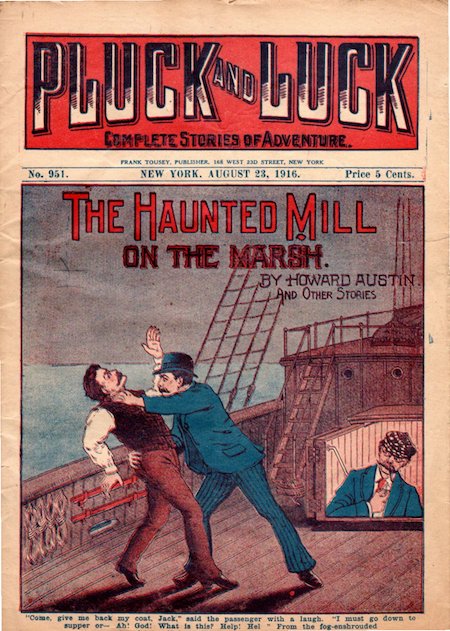

Pluck and Luck was the most persistent of the “dime novels,” racking up 1605 issues between 1898 and 1929. I put “dime novel” in quotes, since it’s somewhat of a misnomer; as you can see, this issue cost a nickel.

It was published by Frank Tousey, a New York publisher responsible for a number of magazines, including Boys of New York, Golden Weekly, Happy Days. Handsome Harry, Wide-Awake Library, and many others. This issue, from August 23, 1916, features “The Haunted Mill on the Marsh,” by Howard Austin, an elaborate adventure story in 24 chapters, printed in minuscule type on 21 pages. The plot involves doubles, a switched baby, an attempt to steal an inheritance, long-lost cousins, a reclusive alchemist, and a mill with hidden rooms. To pander to anti-Semitic readers, the villain is a dastardly French Jew with an elaborate synthetic accent. The style seems dated for the period, but Tousey endlessly recycled his copy, so there’s no telling when it was written.

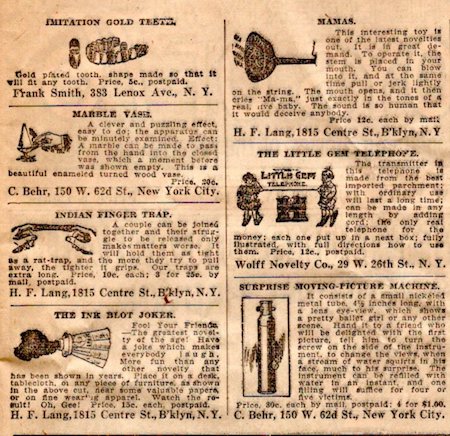

The rest of the 32 pages are filled with two one-page chapters from serial stories (“Making it Pay” and “Simple Sam”), six pages of brief fillers (“Current News,” “From all Points,” “Timely Topics,” “Interesting Articles,” “Items of General Interest,” and “Articles of All Kinds”), and a page of editorial information and “Grins and Chuckles.” The last two pages are ads: the first one small ads for cheap novelties, and the second a full-page ad for the current issue of The Liberty Boys of ’76.

The back cover advertises Tousey’s line of “Ten-Cent Hand Books,” How-To manuals on such diverse skills as ventriloquism, making candy, flirting, boxing, bird-keeping, and dream interpretation.

Here are some of the enticing ads:

Howard Austin, the author of The Haunted Mill on the Marsh, was, as was often the case, a pseudonym; the probable author was Tousey stalwart Francis Worcester Doughty. Doughty also published a curious little pamphlet called Evidences of Man in the Drift (1892), which details his belief that stones he found in New England were actually small sculptures by ancient man. He placed them in the Tertiary Period (from 66 to 2.6 million years ago), which is rather unorthodox. And raises the question: did Richard Shaver know about this?

(Posted by Doug Skinner)