The speaking statue may be a uniquely Italian custom. At any rate, I don’t know of any elsewhere.

By a speaking statue, I don’t mean one that actually talks, but one that serves as a bulletin board for diatribes, slogans, and satirical verse. An essential part of the tradition is that the statue becomes a character, and the squibs hung around its neck or pasted to its pedestal are keyed to its personality. It acts somewhat like a ventriloquial dummy: a comedian who can get away with riskier material than a “real” performer. In the case of the statue, the writer can also stay anonymous; which, given some times and places, has been much safer.

The type specimens are six statues in Rome, often known collectively as il congresso degli arguti, the assembly of wits.

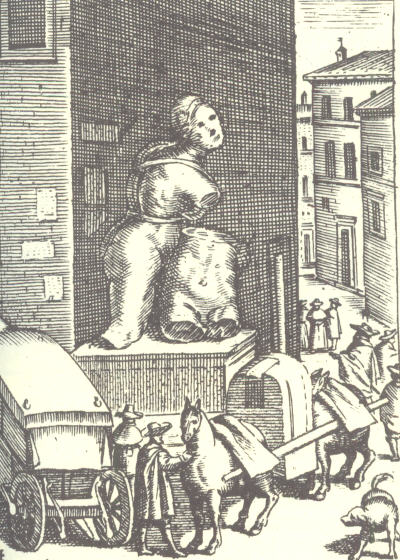

The undisputed leader is Pasquino, shown above in a 17th century engraving. He’s a fragment of classical statuary, unearthed in 1501, and, in true Roman fashion, simply posted on the sidewalk as a public ornament. Nobody is quite sure how he got his name (which, yes, gave us the word “pasquinade”): tradition variously names him after a schoolteacher, a barber, or an innkeeper. For centuries, he’s been mocking popes and politicians, and keeping up a running political commentary, often in Roman dialect.

But Pasquino is not always a monologist. He’s often teamed with a large reclining river god, Marforio (again, explanations for the name vary). They often work frankly as a comedy duo, with Marforio feeding Pasquino straight lines.

Pasquino and Marforio have sometimes angered authorities, both individually and together. They’ve been threatened with being dumped into the Tiber — although exasperated butts of mockery soon realized the river treatment would only rile up the writers.

The two statues have, however, occasionally been watched and guarded, at which times the other four have become more talkative.

Madama Lucrezia (or, in dialect, Lugrezzia) is rather inactive nowadays; but she was the only female, and often offered the woman’s viewpoint. She corresponded with the Abate Luigi, who, sadly, had his head removed repeatedly, and who played the part of an unscrupulous politico. Il Facchino (the Porter), a battered and stout geezer with a barrel, has long been identified with Martin Luther. Il Babuino (dialect for babbuino, baboon) is a particularly homely silenus, whose invective-laden babuinate had a style of their own.

There are a few statue parlanti in other cities. Milan has Scior Capera; Venezia, il Gobbo di Rialto (the Rialto Hunchback); and Florence a stately boar, il Porcellino (the Little Pig). All are local celebrities, with long and illustrious careers.

But are there examples outside Italy? Or do Italians have a particular bond with their public statuary?

Earlier this year, Roman authorities announced plans to fence off the speaking statues, to “protect” them. This hasn’t worked before. The city has offered a website as a substitute. We’ll see what happens.

(Posted by Doug Skinner)